- Home

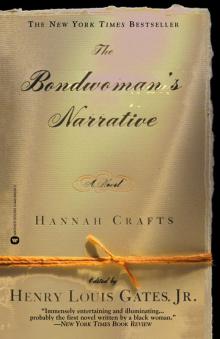

- Hannah Crafts

The Bondwoman's Narrative Page 2

The Bondwoman's Narrative Read online

Page 2

Armed with these assumptions, I decided to attempt to obtain Hannah Crafts’s manuscript. At the time of the auction—February 15, 2001—I was recovering from a series of hip-replacement surgeries and was forbidden to travel. I asked a colleague, Richard Newman, a well-known scholar, librarian, and bibliophile, and the Fellows Coordinator at the W. E. B. Du Bois Institute at Harvard, if he would go in my stead and bid on lot 30. He agreed. We discussed an upper limit on the bid.

The next day I waited expectantly for Dick’s call, fearful that the bidding would far surpass my modest cap on the sale. When no phone call came by the end of office hours, I knew that we had failed to acquire the manuscript. Finally, late that night, Dick phoned. He had waited to call until the auction was complete. His first bid had been accepted, he reported, for far less than the floor proposed in the catalogue. No one else had bid on lot 30. I was astonished.

Dick also told me that he had spoken about the authenticity of the manuscript with Wyatt Houston Day, the only person who had read it in half a century other than Dorothy Porter Wesley. Day had told Dick that he had found “internal evidence that it was written by an African American.” Moreover, he didn’t think that Wesley would have bought it, as it turned out, in 1948—“if she didn’t think it authentic.” He also promised to send me the correspondence between Dorothy and the bookseller from whom she had purchased the manuscript. My suspicion about the curious line in the Swann catalogue description had been confirmed: Dorothy Porter Wesley had indeed believed Hannah Crafts to be black, and so did Wyatt Houston Day. Accordingly, I was even more eager to read the manuscript than I had been initially, and just as eager to read Porter’s thoughts about its origins and her history of its provenance.

It turned out that Porter had purchased the manuscript in 1948 for $85 from Emily Driscoll, a manuscript and autograph dealer who kept a shop on Fifth Avenue. In her catalogue (no. 6, 1948), item number 9 reads as follows:

A fictionalized biography, written in an effusive style, purporting to be the story of the early life and escape of one Hannah Crafts, a mulatto, born in Virginia, who lived there, in Washington, D.C., and Wilmington, North Carolina. From internal evidence it is apparent that the work is that of a Negro who had a narrative gift. Interesting for its content and implications. Believed to be unpublished.

Driscoll dated the manuscript’s origin as “before 1860.” (Wyatt Houston Day, judging from the appearance of the paper and ink as well as internal evidence, had dated it “circa 1850s.”)

Dorothy Porter (she would marry the historian Charles Wesley later) wrote to Driscoll with her reactions to Hannah Crafts’s text. Porter perceptively directed Driscoll’s attention to two of the manuscript’s most distinctive features: first, that it is “written in a sentimental and effusive style” and was “strongly influenced by the sentimental fiction of the mid-Nineteenth Century.” At the same time, however, despite employing the standard conventions of the sentimental novel, which thrived in the 1850s as a genre dominated by women writers, this novel seems to be autobiographical, reflecting “first-hand knowledge of estate life in Virginia,” unlike even those sentimental novels written about the South. Despite this autobiographical element, this text is a novel, replete with the conventions of the sentimental: “the best of the writer’s mind was religious and emotional and in her handling of plot the long arm of coincidence is nowhere spared,” Porter concludes with considerable understatement.

Most important of all, Porter strongly stresses to Driscoll that she is firmly convinced that Hannah Crafts was an African American woman:

The most important thing about this fictionalized personal narrative is that, from internal evidence, it appears to be the work of a Negro and the time of composition was before the Civil War in the late forties and fifties.

Porter arrived at this conclusion not only because of Crafts’s intimate knowledge of plantation life in Virginia but also—and this comment was the most striking of all—because of the subtle, “natural” manner in which she draws black characters.

There is no doubt that she was a Negro because her approach to other Negroes is that they are people first of all. Only as the story unfolds, in most instances, does it become apparent that they are Negroes.

I was particularly intrigued by this observation. Although I had not thought much about it before, white writers of the 1850s (and well beyond) did tend to introduce Negro characters in their works in an awkward manner. Whereas black writers assumed the humanity of black characters as the default, as the baseline of characterization in their texts, white writers, operating on the reverse principle, used whiteness as the default for humanity, introducing even one-dimensional characters with the metaphorical equivalent of a bugle and drum. In Uncle Tom’s Cabin, to take one example, white characters receive virtually no racial identification. Mr. Haley is described as “a short, thick-set man.” Solomon is “a man in a leather apron.” Tom Loker is “a muscular man.” Whiteness is the default for Stowe. Blackness, by contrast, is almost always marked. For example, Mose and Pete, Uncle Tom’s and Aunt Chloe’s sons, are “a couple of wooly headed boys,” similar in description to “wooly headed Mandy.” Aunt Chloe surfaces in the text with a “round black shining face.” Uncle Tom is “a full glossy black,” possessing “a face [with] truly African features.” At one point in the novel “little black Jake” appears. Black characters are almost always marked by their color or features when introduced into Stowe’s novel. Thinking about Stowe’s use of color when introducing black characters forced me to wonder what Porter had meant about Crafts’s handling of the characterization of black people. Porter’s observation was both acute and original.

In response to Porter’s undated letter, Emily Driscoll wrote back on September 27, 1951. After saying she was “delighted” that Porter was keeping the manuscript for her personal collection, Driscoll reveals how she came upon it:

I bought it from a scout in the trade (a man who wanders around with consignment goods from other dealers). Because of my own deep interest in the item as well as the price I paid him I often tried to find out from him where he bought it and all that I could learn was that he came upon it in Jersey!

“It’s my belief,” Driscoll concludes, “that it is based on a substratum of fact, considerably embroidered by a romantic imagination fed by reading those 19th Century novels it so much resembles.” Driscoll, like Porter, believed the book to be an autobiographical novel based on the actual life of a female fugitive slave.

It is difficult to explain how excited I became as I read this exchange of letters. Dorothy Porter was one of the most sophisticated scholars of antebellum black writing; indeed, her work in this area, including both subtle critical commentary and the editing of an anthology that had defined the canon of antebellum black writing, was without peer in her generation of scholars. Because she thought Hannah Crafts to have been black, I wanted to learn more. But Dorothy Porter had apparently not attempted to locate the historical Hannah Crafts; she had, however, located a Wheeler family living in North Carolina “both before and after the war,” the Wheelers being Hannah Crafts’s masters. And, almost in passing, she mentioned to Driscoll that she had come across “one John Hill Wheeler (1806–1882)” who “held some government positions,” presumably in Washington, D.C.

Curious about Dorothy Porter’s report of her instincts, and filing away her observation about the Wheeler who had held government positions, I finally read the manuscript before embarking upon the arduous, detailed search through nineteenth-century U.S. census records for the characters in Crafts’s novel and, indeed, for Crafts herself.

What I read is a fascinating novel about passing, set on plantations in Virginia and North Carolina and in a government official’s residence in Washington, D.C. The novel is an unusual amalgam of conventions from gothic novels, sentimental novels, and the slave narratives. After several aborted attempts to escape, the heroine ends her journey in New Jersey, where she marries a Methodist minister a

nd teaches schoolchildren in a free black community.

I found The Bondwoman’s Narrative a captivating novel for several reasons. If indeed Hannah Crafts turned out to be black, this would be the first novel written by a female fugitive slave, and perhaps the first novel written by any black woman at all. Hannah Crafts’s novel ends with the classic conclusion of a sentimental novel, which can be summarized as “and they lived happily ever after,” unlike Wilson’s novel, which ends with her direct appeal to the reader to purchase her book so that she can retrieve her son, who is in the care of a foster home. Crafts also uses the story of a fugitive slave’s captivity and escape for the elements of her plot, as well as a subplot about passing, two other “firsts” for a black female author in the African American literary tradition.

The Bondwoman’s Narrative contains one of the earliest examples of the topos of babies switched at birth—one black, one white—in African American literature.6 The novel begins with the story of the mulatto mistress of the Lindendale plantation, who tries to pass but is trapped—appropriately enough—by one Mr. Trappe. Her story unfolds in chapter four, “A Mystery Unraveled.” On page 44, Crafts tells us that a nurse had placed her mistress “in her lady’s bed, and by her lady’s side, when that Lady was to[o] weak and sick and delirious to notice[, and] the dead was exchanged for the living.” The natural mother is sold south, the child is reared as white, and Mr. Trappe, who eventually uncovers the truth through his position as the family’s lawyer, uses his knowledge to blackmail Hannah’s mulatto mistress. Mark Twain, among others, would employ a similar plot device in his novel Pudd’nhead Wilson (1894).

The costuming, or cross-dressing, of the character Ellen as a boy (pp. 81–84) foreshadows Hannah’s own method of escape and echoes the method of escape used in real life by the slave couple Ellen and William Craft in December 1848. The sensational story of Ellen’s use of a disguise as a white male was first reported in Frederick Douglass’s newspaper, The North Star, on July 20, 1849.7 William Wells Brown’s novel, Clotel (1853), employed this device, and William Still, in his book, The Underground Railroad (1872), reports similar uses of “male attire” by female slaves Clarissa Davis (in 1854) and Anna Maria Weems (alias Joe Wright) in 1855.8 I wondered if Hannah’s selection of the surname Crafts for her own name could possibly have been an homage to Ellen, as would have been the use of Ellen’s name for the character in her novel.

Hannah Crafts, as a narrator, is at pains to explain to her readers how she became literate. This is a signal feature of the slave narratives, and of Wilson’s Our Nig. She also establishes herself as blessed with the key characteristics of a writer, as someone possessing “a silent unobtrusive way of observing things and events, and wishing to understand them better than I could.” (p. 5)9 “Instead of books,” she continues modestly, “I studied faces and characters, and arrived at conclusions by a sort of sagacity” similar to “the unerring certainty of animal instinct.” (p. 27) She then reveals how she was taught to read and write by the elderly white couple who ran afoul of the law because of their actions. Early in her novel, Crafts remembers that, even as a child, “while the other children of the house were amusing themselves I would quietly steal away from their company to ponder over the pages of some old book or newspaper that chance had thrown in [my] way…. I loved to look at them and think that some day I should probably understand them all.” (pp. 6–7)

Crafts is also remarkably open about her feelings toward other slaves. Her horror and disgust at moving from the Wheeler home to the “miserable” huts of the field slaves, whose lives are “vile, foul, filthy,” her anger at her betrayal by the “dark mulatto” slave Maria with “black snaky eyes” (p. 203), and her description of Jo (p. 133), are among the sort of observations, you will recall, that Dorothy Porter felt underscore the author’s ethnic identity as an African American—that is, the very normality and ordinariness of her reactions, say, to the wretched conditions of slave life or to being betrayed by another black person. Rarely have African American class or color tensions—the tensions between house slaves and field slaves—been represented so openly and honestly as in this novel, foreshadowing similar comments made by writers such as Nella Larsen in the 1920s and 1930s, in another novel about a mulatto and passing:

Here the inscrutability of the dozen or more brown faces, all cast from the same indefinite mold, and so like her own, seemed pressed forward against her. Abruptly it flashed upon her that the harrowing invitation of the past few weeks was a smoldering hatred. Then she was overcome by another, so actual, so sharp, so horribly painful, that forever afterwards she preferred to forget it. It was as if she were shut up, boxed up, with hundreds of her race, closed up with that something in the racial character which had always been, to her, inexplicable, alien. Why, she demanded in fierce rebellion, should she be yoked to these despised black people? (Quicksand, Chapter 10)

Often when reading black authors in the nineteenth century, one feels that the authors are censoring themselves. But Hannah Crafts writes the way we can imagine black people talked to—and about—one another when white auditors were not around, and not the way abolitionists thought they talked, or black authors thought they should talk or wanted white readers to believe they talked. This is a voice that we have rarely, if ever, heard before. Frederick Douglass, William Wells Brown, and Harriet Jacobs, for example, all drew these sort of class distinctions in their slave narratives and fictions (in the case of Douglass and Brown)—even contrasting slaves speaking dialect with those speaking standard English—but toned down, or edited, compared with Hannah Crafts’s more raw version. This is the sort of thing Porter observed that led her initially to posit a black identity for Hannah Crafts.

Crafts, as Porter noted, tends to treat the blackness of her characters as the default, even on occasion signaling the whiteness of her characters, such as little Anna’s “white beautiful arms.” (p. 129) Often we realize the racial identity of her black characters only by context, in direct contrast to Stowe’s direct method of accounting for race as the primary indication of a black character’s identity. When the maid Lizzy is introduced in the novel, we learn that she was “much better educated than” Hannah was, that she was well traveled, and that she had “a great memory for dates and names” before we learn that she was “a Quadroon.” When near the novel’s end we meet Jacob and his sister, two fugitive slaves, Crafts describes them in the following manner: “Directly crossing … were the figures of two people. They were speaking, and the voices were those of a man and a woman.” (pp. 214–215) Only later does she reveal Jacob’s race by reporting that “I opened my eyes to encounter those of a black man fixed on me,” a description necessary to resolve the mystery of the identity of these two people who, it turns out, are fugitive slaves like Hannah. Crafts, a visual narrator who loves to use language to paint landscapes and portraits of her characters, in the most vivid manner, does distinguish among the colors and characteristics, the habits and foibles, of the black people in her novel—one woman, she tells us, has “a withered smoked-dried face, black as ebony” (p. 139)—but she tends to do so descriptively, as a keen if opinionated observer from within. Crafts even describes her fellow slave Charlotte as “one every way my equal, perhaps my superior” (p. 136), which would have been a remarkable leap for a white writer to make.

When she describes the wedding of Mrs. Henry’s “favorite slave,” she tells us about “[q]ueer looking old men,” then adds a description of their “withered and puckered” black faces that “contrasted strangely with their white beards.” Similarly, we see “fat portly dames” and then learn of their “ebony complexions” only as contrast to their “turbans of flaming red” and “gay clothes of rainbow colors.” (p. 119) The color of her characters here is called upon to paint a picture; Stowe, by contrast, almost never uses a black character’s color in this way. For Stowe, it is their defining marker of identity. For Crafts, slaves are always, first and last, human beings, “people” as she frequen

tly puts it. (pp. 199–215) Similarly, Crafts tells us that she was betrayed by a slave named Maria, “a wary, powerful, and unscrupulous enemy.” It is only after describing Maria’s attributes as an antagonist that Crafts thinks to tell us that she was “a dark mulatto, very quick motioned with black snaky eyes,” physical characteristics rendered here as outward reflections of her inner personality. Even for a well-meaning abolitionist author such as Harriet Beecher Stowe, the reverse was often true: the sign of blackness or race predetermined the limited range of characteristics even possible for a black person to possess. The difference is a subtle one, but crucial. Occasionally, Crafts does not disclose the color or physical features of her black characters at all, as in her depiction of her mother and her husband in the final chapter of her novel (pp. 237–239). Few, if any, white novelists demonstrated this degree of ease or comfort with race in antebellum American literature.

As the scholar Augusta Rohrbach pointed out to me, Crafts’s novel manifests a surprisingly sophisticated storytelling technique—such as the way she relinquishes her tale on two occasions to the character, Lizzy (pp. 34, 172), only to reinsert herself after Lizzy’s tale (which “made the blood run cold to hear”) has finished.10 But the novel also contains “all the clumsy plot structures, changing tenses, impossible coincidences and heterogeneous elements of the best” of the sentimental novels, as the critic Ann Fabian noted when I showed her the manuscript.11 It is the combination, the unfinished blend of its clashing styles, that points to the untutored and self-educated level of the author’s writing abilities, reflected in her vocabulary, in her spelling errors, in her uneven use of punctuation, in her narrative techniques, and in the clash of rhetorical devices borrowed from gothic and sentimental novels and the slave narratives.

The Bondwoman's Narrative

The Bondwoman's Narrative