- Home

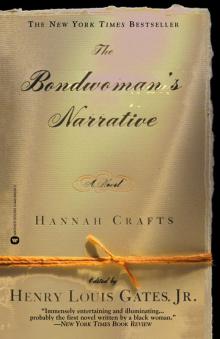

- Hannah Crafts

The Bondwoman's Narrative

The Bondwoman's Narrative Read online

Copyright

Copyright © 2002 by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

All rights reserved.

Warner Books, Inc.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com.

First eBook edition: April 2002

ISBN: 978-0-7595-2764-5

CONTENTS

COPYRIGHT

INTRODUCTION

PREFACE

EPIGRAPH

CHAPTER 1: In Childhood

CHAPTER 2: The Bride And T he Bridal Company

CHAPTER 3: Progress In Discovery

CHAPTER 4: A Mystery Unraveled

CHAPTER 5: Lost, Lost, Lost

CHAPTER 6: New Places

CHAPTER 7: Mr Trappe

CHAPTER 8: A New Master

CHAPTER 9: The Slave-trader

CHAPTER 10: The Henry Family

CHAPTER 11: An Elopement

CHAPTER 12: A New Mistress

CHAPTER 13: A Turn of The Wheel

CHAPTER 14: Lizzy’s Story

CHAPTER 15: Lizzy’s Story Continued

CHAPTER 16: In North Carolina

CHAPTER 17: Escape

CHAPTER 18: Strange Company

CHAPTER 19: An Old Friend

CHAPTER 20: Retribution

CHAPTER 21: In Freedom

TEXTUAL ANNOTATIONS

APPENDIX A

APPENDIX B

APPENDIX C

A NOTE ON CRAFTS’S LITERARY INFLUENCES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

ALSO BY HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR.

The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American

Literary Criticism

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Man

The African-American Century: How Black Americans

Have Shaped Our Country (with Cornel West)

Colored People: A Memoir (with Cornel West)

Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American

Experience (with Kwame Anthony Appiah)

EDITED BY HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR.

Our Nig; or, Sketches from the Life of a Free Black by Harriet E. Wilson

In memory

of

Dorothy Porter Wesley,

1905–1995

on whose shoulders

we stand.

INTRODUCTION

The Search for a Female Fugitive Slave

Each year, Swann Galleries conducts an auction of “Printed & Manuscript African-Americana” at its offices at 104 East Twenty-fifth Street in New York City. I have the pleasure of receiving Swann’s annual mailing of the catalogue that it prepares for the auction. The catalogue consists of descriptions of starkly prosaic archival documents and artifacts that have managed, somehow, to surface from the depths of the black past. To many people, the idea of paging through such listings might seem as dry as dust. But to me, there is a certain poignancy to the fact that these artifacts, created by the disenfranchised, have managed to survive at all and have found their way, a century or two later, to a place where they can be preserved and made available to scholars, students, researchers, and passionate readers.

The auction is held, appropriately enough, in February, the month chosen in 1926 by the renowned historian Carter G. Woodson to commemorate and encourage the preservation of African American history. (Woodson selected February for what was initially Negro History Week, because that month contained the birth dates of two presidents, George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, as well as that of Frederick Douglass, the great black abolitionist, author, and orator.)

For our generation of scholars of African American Studies, African American History Month is an intense period of annual conferences and commemorations, endowed lecture series and pageants, solemn candlelight remembrances of our ancestors’ sacrifices for the freedom we now enjoy—especially the sacrifices of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.—and dinners, concerts, and performances celebrating our people’s triumphs over slavery and de jure and de facto segregation. We have survived, we have endured, indeed, we have thrived, Black History Month proclaims, and our job as Carter Woodson’s legatees is, in part, to remind the country that “the struggle continues” despite how very far we, the descendants of African slaves, have come.

Because of time constraints, I usually participate in the auction by telephone, if at all, despite the fact that I devour the Swann catalogue, marking each item among its nearly four hundred lots that I would like to acquire for my collection of Afro-Americana (first editions, manuscripts, documents, posters, photographs, memorabilia) or for the library at my university.

This year’s catalogue was no less full than last year’s, reflecting a growing interest in seeking out this kind of material from dusty repositories in crowded attics, basements, and closets. I made my way through it leisurely, keeping my precious copy on the reading stand next to my bed, turning to it each night to fall asleep in wonder at the astonishing myriad array of artifacts that surface, so very mysteriously, from the discarded depths of the black past. Item number 20, for example, in this year’s catalogue is a partially printed document “ordering several men to surrender a male slave to the sheriff against an unpaid debt.” The slave’s name was Aron, he was twenty-eight years of age, and this horrendous event occurred in Lawrence County, Alabama, on October 30, 1833. Lot 24 is a manuscript document that affirms the freed status of Elias Harding, “the son of Deborah, a ‘coloured’ woman manumitted by Richard Brook … [attesting] that he is free to the best of [the author’s] knowledge and belief.” Two female slaves, Rachel and Jane, mother and daughter, were sold for $500 in Amherst County, Virginia, on the thirteenth of October in 1812 (lot 13). The last will and testament (dated May 9, 1825) of one Daniel Juzan from Mobile, Alabama, leaves “a legacy for five children he fathered by ‘Justine a free woman of color who, now, lives with me’” (lot 17). These documents are history-in-waiting, history in suspended animation; a deeply rich and various level of historical detail lies buried in the pages of catalogues such as this, listing the most obscure documents that some historian will one day, ideally, breathe awake into a lively, vivid prose narrative. Dozens of potential Ph.D. theses in African American history are buried in this catalogue.

Among this year’s bounty of shards and fragments of the black past, one item struck me as especially interesting. It was lot 30 and its catalogue description reads as follows:

Unpublished Original Manuscript. Offered by Emily Driscoll in her 1948 catalogue, with her description reading in part, “a fictionalized biography, written in an effusive style, purporting to be the story, of the early life and escape of one Hannah Crafts, a mulatto, born in Virginia.” The manuscript consists of 21 chapters, each headed by an epigraph. The narrative is not only that of the mulatto Hannah, but also of her mistress who turns out to be a light-skinned woman passing for white. It is uncertain that this work is written by a “negro.” The work is written by someone intimately familiar with the areas in the South where the narrative takes place. Her escape route is one sometimes used by run-aways.

The author is listed as Hannah Crafts, and the title of the manuscript as “The Bondwoman’s Narrative by Hannah Crafts, a Fugitive Slave, Recently Escaped from North Carolina.” The manuscript consists of 301 pages bound in cloth. Its provenance was thought to be New Jersey, “circa 1850s.” Most intriguing of all, the manuscript was being sold from “the library of historian/bibliographer Dorothy Porter Wesley.”

Three things struck me immediately when I read the catalogue description of lot 30. The first was that this manuscript had emerged from the monumental private coll

ection of Dorothy Porter Wesley (1905–95), the highly respected librarian and historian at the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University. Porter Wesley was one of the most famous black librarians and bibliophiles of the twentieth century, second only, perhaps, to Arthur Schomburg, whose collection constituted the basis of the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library, which is now aptly named after him. Among her numerous honors was an honorary doctorate degree from Radcliffe; Harvard’s W. E. B. Du Bois Institute for Afro-American Research annually offers a postdoctoral fellowship endowed in Porter Wesley’s name. Her notes about the manuscript, if she had left any, would be crucial in establishing the racial identity of the author of this text.

The second fact that struck me was far more subtle: the statement that “it is uncertain that this work is written by a ‘negro’” suggests that someone—either the authenticator for the Swann Galleries, who turns out to have been Wyatt Houston Day, a distinguished dealer in Afro-Americana, or Dorothy Porter Wesley herself—believed Hannah Crafts to have been black. Moreover, the catalogue reports that “the work is written by someone intimately familiar with the areas in the South where the narrative takes place.” So familiar was she, in fact, with the geography of the region that, the description continues, “her escape route is one sometimes used by run-aways.” This was the third and most telling fact, suggesting that the author had used this route herself. If the author was black, then this “fictionalized slave narrative”—an autobiographical novel apparently based upon a female fugitive slave’s life in bondage in North Carolina and her escape to freedom in the North—would be a major discovery, possibly the first novel written by a black woman and definitely the first novel written by a woman who had been a slave. (Harriet E. Wilson’s Our Nig, published in 1859, ignored for a century and a quarter, then rediscovered and authenticated in 1982, is the first novel published by a black woman. Unlike Hannah Crafts, however, Wilson had been born free in the North.)

Just as exciting was the fact that this three-hundred-page holograph manuscript was unpublished. Holograph, or handwritten, manuscripts by blacks in the nineteenth century are exceedingly rare, an especially surprising fact given that hundreds of African Americans published books—slave narratives, autobiographies, religious tracts, novels, books of poems, anti-slavery political tracts, scientific works, etc.—throughout the nineteenth century. Despite the survival of this large body of writing, to my knowledge no holograph manuscripts survive for belletristic works, such as novels, or for the slave narratives, even by such bestselling authors as Frederick Douglass, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, or William Wells Brown. And because most of the slave narratives and works of fiction published before the end of the Civil War were edited, published, and distributed by members of the abolitionist movement, scholars have long debated the extent of authorship and degree of originality of many of these works. To find an unedited manuscript, written in an exslave’s own hand, would give scholars an unprecedented opportunity to analyze the degree of literacy that at least one slave possessed before the sophisticated editorial hand of a printer or an abolitionist amanuensis performed the midwifery of copyediting. No, here we could encounter the unadulterated “voice” of the fugitive slave herself, exactly as she wrote and edited it.

One other thing struck me about Hannah Crafts’s claim to authorship as “a fugitive slave,” as she puts it in the subtitle of her manuscript. Fewer than a dozen white authors in the nineteenth century engaged in literary racial ventriloquism, adopting a black persona and claiming to be black. Why should they? Harriet Beecher Stowe had redefined the function—and the economic and political potential—of the entire genre of the novel by retaining her own identity and writing about blacks, rather than as a black. While it is well known that Uncle Tom’s Cabin sold an unprecedented 300,000 copies between March 20, 1852, and the end of the year, even Stowe’s next anti-slavery novel, Dred, sold more than 100,000 copies in one month alone in 1856.1 There was no commercial advantage to be gained by a white author writing as a black one; Stowe sold hundreds of thousands more copies of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Dred than all of the black-authored slave narratives combined, despite the slave narrative’s enormous popularity, and had no need to disguise herself as a black author.

The artistic challenge of creating a fictional slave narrative, purportedly narrated or edited by an amanuensis, did appeal to a few writers, however, as the scholars Jean Fagan Yellin and William L. Andrews have shown.2 As early as 1815, Legh Richmond published a novel in Boston titled The Negro Servant: An Authentic and Interesting Narrative, which, Richmond claims in the novel’s subtitle, had been “Communicated by a Clergyman of the Church of England.” Nevertheless, these fictionalized slave narratives were published with the identity of a white “editor’s” or printer’s presence signified on the title or copyright page, thereby undermining the ruse by drawing attention to the true author’s identity as a white person. And even the most successful of these novels, Richard Hildreth’s popular novel, The Slave: or Memoirs of Archy Moore (1836), was consistently questioned in reviews.3

Similarly, in the case of the sole example of a female fictionalized slave narrative—Mattie Griffith’s Autobiography of a Female Slave, published anonymously in October 1856—“few readers seemed to credit the narrative voice as one that belonged to a former slave,” as the editor of a recent edition, Joe Lockard, concludes from a careful examination of contemporary reviews. Accordingly, Griffith revealed her identity as a white woman within weeks of the book’s publication, in part because reviews, such as one published in the Boston Evening Transcript on December 3, 1856, argued that the work could only be taken as the work of “some rabid abolitionist.”4

Moreover, reading these ten slave narrative novels today reveals their authors often to be firmly in the grip of popular nineteenth-century racist views about the nature and capacities of their black characters that few black authors could possibly have shared, as in this example from Griffith’s novel:

Young master, with his pale, intellectual face, his classic head, his sun-bright curls, and his earnest blue eyes, sat in a half-lounging attitude, making no inappropriate picture of an angel of light, whilst the two little black faces seemed emblems of fallen, degraded humanity. [p. 113]

Griffith’s passage—as Jean Yellin notes—echoes one from Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

There stood the two children, representatives of the two extremes of society. The fair, high-bred child, with her golden head, her deep eyes, her spiritual, noble brow and prince-like movements; and her black, keen, subtle, cringing, yet acute neighbor. They stood the representatives of their races. The Saxon, born of ages of cultivation, commands, education, physical and moral eminence; the Afric, born of ages of oppression, submission, ignorance, toil, and vice. (Chapter 20)5

Or this exchange purportedly between Griffith’s mulatto heroine and the slave Aunt Polly:

“Oh child,” she begun [sic], “can you wid yer pretty yallow face kiss an old pitch-black nigger like me?”

“Why, yes, Aunt Polly, and love you too; if your face is dark I am sure your heart is fair.” [p. 55]

Whereas several black authors of the slave narratives drew sharp class and intellectual distinctions between house and field slaves, and sometimes indicated these differences by color and dialect (I am thinking here of Frederick Douglass, Harriet Jacobs, William Wells Brown, among others), rarely did they allow themselves to be caught in the web of racist connotations associated with slaves, blackness, and the “natural capacities” of persons of African descent, as often did the handful of white authors in antebellum America attempting to adopt a black persona through a novel’s narrator.

It occurred to me as I studied the Swann catalogue that another telling feature of this manuscript that would be essential to establishing the racial identity of its author would be the absence or presence of the names of real people—that is, people or characters who had actually existed and whom the author had known herself. Novels pr

etending to be actual autobiographical slave narratives rarely use anything but fictional names for their characters, just as Harriet Beecher Stowe does, even if Stowe had based her characters on historical sources, including authentic slave narratives, as she revealed in The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin; Presenting the Original Facts and Documents Upon Which the Story Is Founded (1853). In other words, no white author had written a fictionalized slave narrative that used as the names of characters the real names of people who had actually existed. Nor had a white author created a fiction of black slave life that either did not read “like a novel,” falling outside of the well-established conventions of the slave narrative as a genre, or did not unconsciously reflect racist assumptions about black people, flaws even more glaring because of the author’s hatred of the institution of slavery.

Nor did a nineteenth-century white writer, attempting these acts of literary minstrelsy or ventriloquism, successfully “pass for black.” Just as the minstrels in the nineteenth century—or Al Jolson, Mae West, Elvis Presley, and Eminem in the twentieth century—undertook the imitation of blackness to one degree or another, few of the contemporaries of these authors confused their fictional narrators with real black people. Whereas numerous black people have been taken for white, including the extremely popular twentieth-century historical novelist Frank Yerby or the critic Anatole Broyard, in acts of literary ventriloquism, virtually no white nineteenth-century author successfully passed for black for very long. My fundamental operating principle when engaged in this sort of historical research is that if someone claimed to have been black, then they most probably were, since there was very little incentive (financial or otherwise) for doing so.

The Bondwoman's Narrative

The Bondwoman's Narrative