- Home

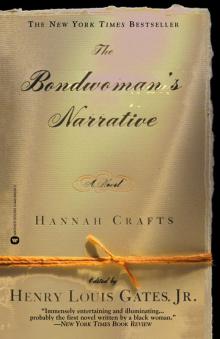

- Hannah Crafts

The Bondwoman's Narrative Page 6

The Bondwoman's Narrative Read online

Page 6

What is clear is that the portrait Crafts draws of Wheeler and the portrait that Wheeler unwittingly sketches of himself are remarkably similar. In other words, there can be little doubt that the author of The Bondwoman’s Narrative, as Dr. Nickell argues in his authentication report, was intimately familiar with Mr. and Mrs. John Hill Wheeler.

Searching for Hannah Crafts

In the U.S. census of 1860 for Washington, D.C., John Hill Wheeler is listed as the head of household, occupation “clerk.” Wheeler has no slaves. What this means in our search for Hannah Crafts is that sometime between 1855, when Jane Johnson liberated herself in Philadelphia, and the taking of this census in Washington in 1860, the slave the Wheelers purchased after Jane escaped, like Jane, escaped to the North and wrote an autobiographical novel about her bondage and her freedom. Judging from evidence in Wheeler’s diary, it seems reasonable to conclude that her escape occurred between March 21 and May 4, 1857. If these assumptions are correct, as I believe the manuscript and documentary evidence suggest, then Hannah Crafts was living in the gravest danger of being discovered by Wheeler and returned to her enslavement under the Fugitive Slave Act. Under this act, as David Brion Davis writes, “any citizen could be drafted into a posse and any free black person seized without a jury trial.”26

Wheeler had sued to recover Jane, Daniel, and Isaiah Johnson under this act, which entitled slaveholders to retrieve fugitive slaves even in the North. The passage of the act led several well-known fugitive slaves—William and Ellen Craft, and Henry “Box” Brown, among them—to flee to Canada or England. (The Crafts went to both.) The Fugitive Slave Act effectively sought to cancel the states north of the Mason-Dixon Line as a sanctuary against human bondage; it meant that privileged fugitive slaves, such as Harriet Jacobs, were forced to allow friends to purchase their freedom from their former masters. But for most of the slaves who had managed to make their way by foot to the North, it meant a life of anxiety, fear, disguise, altered identity, changes of name, and fabricated pasts. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made life in the northern free states—like freedom itself—a necessary tabula rasa for many fugitive slaves, and a state of being fundamentally imperiled.

I began this search for Hannah Crafts because I was intrigued by the notes left by the scholar and librarian Dorothy Porter concerning her belief that Crafts was both a black woman and a fugitive slave, all of which made me want to learn more. Although Porter purchased the manuscript in 1948 from a rare-book dealer in New York City, the manuscript had been located by a “book scout” in New Jersey. Since Crafts claims at the end of the tale to be living in a free colored community in New Jersey, it seemed reasonable to continue my search for her there.

The obvious name for which to search, as you might expect, was Hannah Crafts. But no Hannah Craftses are listed in the entire U.S. federal census between 1860 and 1880. Several women named Hannah Craft, however, are listed in the 1860 census index. As I would learn as my research progressed, much to my chagrin, Hannah Craft was a remarkably popular name by the middle of the nineteenth century. All of these Hannah Crafts were white, and none had lived in the South. But one Hannah Craft was indeed living in New Jersey in 1860. I eagerly searched for her in the census records. She was living in the town of Hills-borough, in Somerset County. She was thirty-four years of age and was married to Richard Craft. Both were white. This Hannah Craft was not living in New Jersey before 1860. And her entry listed no birthplace, the sole entry on this page of the census in which this information was lacking. I could not help but wonder if this Hannah Craft could be passing for white, “incognegro,” as it were, given her imperiled and vulnerable status as a fugitive slave.

While I was trying to determine if the Hannah Craft living in New Jersey in 1860 could be passing, it suddenly occurred to me to broaden my search to 1880. After all, if Hannah Crafts had been in her mid to late twenties when she wrote her novel (Frederick Douglass was twenty-seven when he published his 1845 slave narrative), then she would be between fifty-five or so and sixty in 1880, assuming that she had survived. Perhaps I would find her there, living openly under her own name, now that slavery—and the Fugitive Slave Act—was long dead.

To my astonishment, one Hannah Kraft (spelled with a k) was listed as living in Baltimore County, Maryland, in 1880. She was married to Wesley Kraft. (How clever, I thought, to have rendered her husband, Wesley, metaphorically as a Methodist minister— after John Wesley—in her novel!) Both Wesley and Hannah were listed as black. What’s more, Hannah claimed to have been born in Virginia, just as the author of The Bondwoman’s Narrative had been! This had to be Hannah Crafts herself, at last. I was so ecstatic that I took my wife, Sharon Adams, and my best friend and colleague, Anthony Appiah, out to celebrate over a bit too much champagne shortly after ordering a copy of the actual census record for this long-lost author. We had a glorious celebration.

Three days later, the photocopy of the page in the 1880 census arrived from the Mormon Family History Library in Salt Lake City. I stared at the document in disbelief: not only was Hannah said to be thirty years of age—born in 1850, while the novel had been written between 1855 and 1861—but the record noted that this Hannah Kraft could neither read nor write! Despite all of the reasons that census data were chock full of errors, there were far too many discrepancies to explain away to be able to salvage this Hannah Kraft as the possible author of The Bondwoman’s Narrative. My hangover returned.

In the midst of my growing frustration, I examined the Freedman’s Bank records, made newly available on CD-ROM by the Mormon Family History Library. The Freedman’s Bank was chartered by Congress on March 3, 1865. Founded by white abolitionists and businessmen, it absorbed black military banks and sought to provide a mutual savings bank for freed people. By 1874 there were 72,000 depositors with over $3 million. The bank’s white trustees amended the charter to speculate in stocks, bonds, real estate, and unsecured loans. In the financial panic of 1873, the bank struggled to survive, and Frederick Douglass was named president in a futile attempt to maintain confidence. The bank collapsed on June 2, 1874, with most depositors losing their entire savings.

While no Hannah Craft or Crafts appears in the index of the bank’s depositors, a Maria H. Crafts does. Her application, dated March 30, 1874, lists her as opening an account in a bank in New Orleans. Her birthplace is listed as either Massachusetts or Mississippi (the handwriting is not clear), and she identified herself as a schoolteacher. Her complexion is listed as “white,” a designation meaning, as an official at the Mormon Library explained to me, that she could possibly have been white, but this was unlikely, given the fact that Freedman’s was a bank for blacks.27 A far more likely possibility is that she could have been a mulatto, perhaps an especially fair mulatto. Most interesting of all, she has signed the document herself.

I immediately sent a copy of this document to Dr. Joe Nickell for a comparison with the handwriting of the author of The Bond-woman’s Narrative. Dr. Nickell reported that the results were inconclusive. According to Nickell, “the handwriting is a similar type, with some specific differences, notably the lack of the hook on the ending of the s, and a missing up-stroke on the capital c. But the matter is complicated by the fact that we don’t actually have a signature for Hannah Crafts, we only have an instance of her name written in her handwriting on the novel’s title page.” “For some people,” Nickell continued, “there is a marked difference. Because of the lapse of twenty years, during which time her handwriting may have changed, and because we are not comparing signature to signature, we cannot rule out the possibility that this is the handwriting of the same person.”

With this cautiously promising assessment, I returned to the census records in search of Maria H. Crafts. Although twenty-three Mary H. Craftses are listed as “black” in the 1880 national index to the federal census, and six Mary Craftses are listed as mulatto, no Maria Craftses are listed. (Of these Mary Craftses, only one, listed as having been born in Virginia in 1840, could

possibly be our author.) And in the case of Mary H. Crafts we have no record of what the initial H stands for. Still, the handwriting similarities are intriguing, as is the fact that this Maria H. Crafts was a schoolteacher, and hence a potential author.

I now decided to return to an early lead that had once seemed extremely promising. While typing the manuscript, my research assistant, Nina Kollars, suggested that I look for Hannah under the name of Vincent, since she was a slave of the Vincents’ in Virginia, and could have taken Vincent as her surname. (My surname is Gates, I happen to know, because a farmer named Brady living in western Maryland purchased a small group of slaves from Horatio Gates in Berkeley Springs, Virginia, now West Virginia.) So I began to search for Hannah Vincent in the 1850 and 1860 censuses. To my great pleasure, I found Hannah Ann Vincent, age twenty-two, single, living in Burlington, New Jersey, in 1850 in a household that included another woman, named Mary Roberts. Vincent was twenty-two; Roberts, forty-seven. Roberts was black; Vincent was a mulatto, birthplace unknown. I was convinced that this Hannah Vincent was the author of The Bondwoman’s Narrative—that is, until I received Dr. Nickell’s conclusive report. I shelved this theory, since the author of the novel was a slave of the Wheelers’ who had been purchased in 1855 or so because Jane Johnson had run away. Besides, no Hannah Vincent appears in the 1860 New Jersey census.

Because Hannah Crafts claims to be living in New Jersey at novel’s end, in a community of free blacks, married to a Methodist clergyman, teaching schoolchildren, I decided in a last-ditch effort to research the history of black Methodists in New Jersey, taking Crafts at her word. (The obvious problem with an autobiographical novel is determining where fact stops and fiction starts. Still, the New Jersey provenance of the manuscript in 1948 supported this line of inquiry.) What is especially curious about Crafts’s selection of New Jersey as her home in the North is that New Jersey “was the site of several Underground Railroad routes” and that “the region became a haven for slaves escaping the South,” as Giles R. Wright puts it in his Afro-Americans in New Jersey.28 Moreover “by 1870, New Jersey had several all-black communities,” including Skunk Hollow in Bergen County; Guineatown, Lawnside, and Saddlerstown in Camden County; Timbuctoo in Burlington County; and Gouldtown and Springton in Cumberland County. In addition, Camden, Newton, Center, Burlington, Deptford, Mannington, Pilesgrove, and Fairfield also “had a sizeable number of Afro-Americans.” (p. 38) It is, therefore, quite possible that Crafts was familiar with these communities and that she either lived in one or chose to end her novel there because of New Jersey’s curious attraction for fugitive slaves. Yet, few, if any, authors of the slave narratives end their flight to freedom in New Jersey, making it difficult to imagine how Crafts knew about these free black communities as a safe haven from slavery if she did not indeed live in or near one. She did not, in other words, select New Jersey from a reading of slave narratives or abolitionist novels. Slave narrators such as Douglass, Brown, and Jacobs end their flight to the North in places such as Rochester, New Bedford, Boston, or New York.

Joseph H. Morgan’s book, titled Morgan’s History of the New Jersey Conference of the A.M.E. Church, published in Camden, New Jersey, in 1887, lists every pastor in each church within the conference since the church’s founding, as well as each congregation’s trustees, stewards, stewardesses, exhorters, leaders, organists, local preachers, officers, and Sunday school teachers.29

Hannah Vincent was listed in the church at Burlington as a stewardess, church treasurer, and teacher. (The church was named the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, located on East Pearl Street in Burlington, and was founded in 1830.) Could this Hannah Vincent be the person who was living in Burlington in 1850? I presumed so, but checked anyway.

I turned to the 1870 and 1880 federal census records from New Jersey. Hannah Vincent, age forty-six in 1870, was living in the household of Thomas Vincent, age forty-eight. He was listed as black, she as a mulatto. He was a porter in a liquor store, she was “keeping house.” Both were said to have been born in Pennsylvania. Since the Hannah Vincent I had found in 1850 had been listed as twenty-two, single, and a mulatto, I presumed this Hannah Vincent (age forty-six) to be the same person, living with her brother, twenty years later. But in the 1880 census, Hannah—now claiming that her age was still forty-eight!—is listed as Thomas’s wife, both now identified as having been born in New Jersey. Unless the 1850 Hannah Vincent had married a man also named Vincent, this Methodist Sunday school teacher was a different person from her 1850 namesake. To add to the confusion, a birth record for a Samuel Vincent, dated 1850, lists his parents as one Thomas and Hannah, despite the fact that our Hannah Vincent was single according to the 1850 census. Samuel Vincent’s race is not identified. Only her marriage certificate could reveal her maiden name. But a search of the New Jersey marriage licenses stored in Trenton failed to uncover a record of Thomas’s marriage to Hannah. Neither did a search of the tombstones at Bethel A.M.E. Church in Burlington found in the cemetery adjacent to the church uncover the graves of the Vincents.30 Unless a marriage certificate, death records of their children, or some other document appears, we won’t be able to ascertain the maiden name of this Hannah Vincent. But given the Methodist and Vincent connections, this person remains a candidate as the author of The Bondwoman’s Narrative.

Why did Hannah Crafts fail to publish her novel? Publishing at any time is extraordinarily difficult, and was especially so for a woman in the nineteenth century. For an African American woman, publishing a book was virtually a miraculous event, as we learned from the case of Harriet Wilson. If Hannah Crafts had indeed passed for white and retained her own name once she arrived in New Jersey, then obviously she would not have wanted to reveal her identity or her whereabouts to John Hill Wheeler, who would have tried to track her down, just as he longed to do with Jane Johnson. Even if she changed her name and pretended to be simply writing a novel, the manuscript is so autobiographical that the copyright page would have revealed her new identity and would have led to her exposure.

Ann Fabian speculates that “perhaps she composed her narrative in the late 1850s and by the time” she finished it, saw she had missed the market as she watched a white abolitionist readership and the cultural infrastructure it supported dissolve and turn elsewhere. By the time the war was over, maybe she too was doing other things and never returned to a story “she had written in and for a cultural world of the 1840s and 1850s.” The failure to publish is all the more puzzling, she continues, because the novel does not read as if she were “writing this for herself,” since “it is not an internal sort of story (she doesn’t grow or change) which makes me want to think of her imagining a public for it.” Crafts obviously wanted the story of her life preserved at least for a future readership, because she preserved the manuscript so carefully, as apparently did several generations of her descendants. These facts make her inability to publish her manuscript all the more poignant.

Nina Baym suggests that her decision to write a first-person autobiographical novel could have made publication difficult in the intensely political climate of the anti-slavery movement of the 1850s. Veracity was everything in an exslave’s tale, essential both to its critical and commercial success and to its political efficacy within the movement. As Baym argues:

The first-person stance is also a possible explanation for her not trying to publish it. Given the public insistence on veracity in the handling of slave experiences (you know all those accusations about black fugitive speakers being frauds), she might well have hesitated after all to launch into the marketplace an experimental novel in the first person under her own name.31

As soon as pro-slavery advocates could discredit any part of it as a fiction, “the work and its author,” Baym concludes, “would be discredited. But if she offered it as a fiction pure and simple, it would be ignored.” Regardless of the reasons this book was never published, one thing seems certain: the person who wrote this book knew John Hill Wheeler and his wife

personally, hated them both for their pro-slavery feelings and their racism, and wanted to leave a record of their hatred for posterity.

I have to confess that I was haunted throughout my search for Hannah Crafts by Dorothy Porter’s claim that—judging from internal evidence—Hannah Crafts was a black woman because of her peculiar, or unusually natural, handling of black characters as they are introduced to the novel: “her approach to other Negroes,” we recall that Porter wrote to Emily Driscoll, is “that they are people first of all.” “Only as the story unfolds, in most instances,” she concludes, “does it become apparent that they are Negroes.” While speculation of this sort is risky, what can we ascertain about Hannah Crafts’s racial identity from internal evidence more broadly defined?

It is important to remember that Hannah Crafts is a prototype of the tragic mulatto figure in American and African American literature, which would become a stock character at the turn of the century. She is keenly aware of class differences within the slave community and makes no bones about describing the unsanitary living conditions of the field hands in their cramped quarters with far more honesty, earthiness, and bluntness than I have encountered in either the slave narratives or novels of the period. These descriptions are remarkably realistic and are quite shocking for being so rare in the literature. Whereas Crafts clings to her class orientation as an educated mulatto, as a literate house slave, she does not, on the other hand, reject intimate relationships with black people tout court. She is a snob, in other words, but she is not a racist.

The Bondwoman's Narrative

The Bondwoman's Narrative